Write a postmortem like a Senior Engineer

Turn postmortems into leadership signals with this guide and template. Show impact, boost visibility, and accelerate your engineering career.

Most people treat a postmortem as an exercise to find the root cause. Once they find it, it's finished.

They write it as if it were their raw investigation notes. That's fine for a ticket update, but it's a missed opportunity for a high-visibility document.

A postmortem is not just a technical report. It is your chance to demonstrate technical depth, systems thinking, leadership communication, task prioritization, and forward-looking vision for your systems.

⭐ In this post, you'll learn

How to turn incidents into proof of leadership

How to write postmortems that get you noticed

A checklist for your next postmortem for premium subscribers

🧨 Turn a crisis into career capital

Incidents are moments where visibility is forced. Everyone watches who shows up and how they act. That is the moment to lead.

When I volunteered to write a postmortem for an incident that had no clear owner, I took control of a situation that could have damaged my reputation. I understood the root cause and knew I could close it. That single action made me the face of the resolution. Perception matters. Volunteering flipped the story from “who caused this?” to “who fixed it?”

I have done this before. I used the postmortem as a tool to shape how leadership interpreted the event. In my one-on-one with my manager, there was no blame. I had taken action early, kept updates flowing, and managed the narrative. If I had stayed silent, the environment would have been one of guilt and lack of ownership. Once reputational damage happens, proving innocence later does not matter.

Even when some incidents only affected internal users, I treated it like a production issue. Regular updates every 15 minutes, clear steps, a mitigation-first mindset, and a small postmortem to close this incident. That should be the baseline for all of us. That is how you signal senior standards.

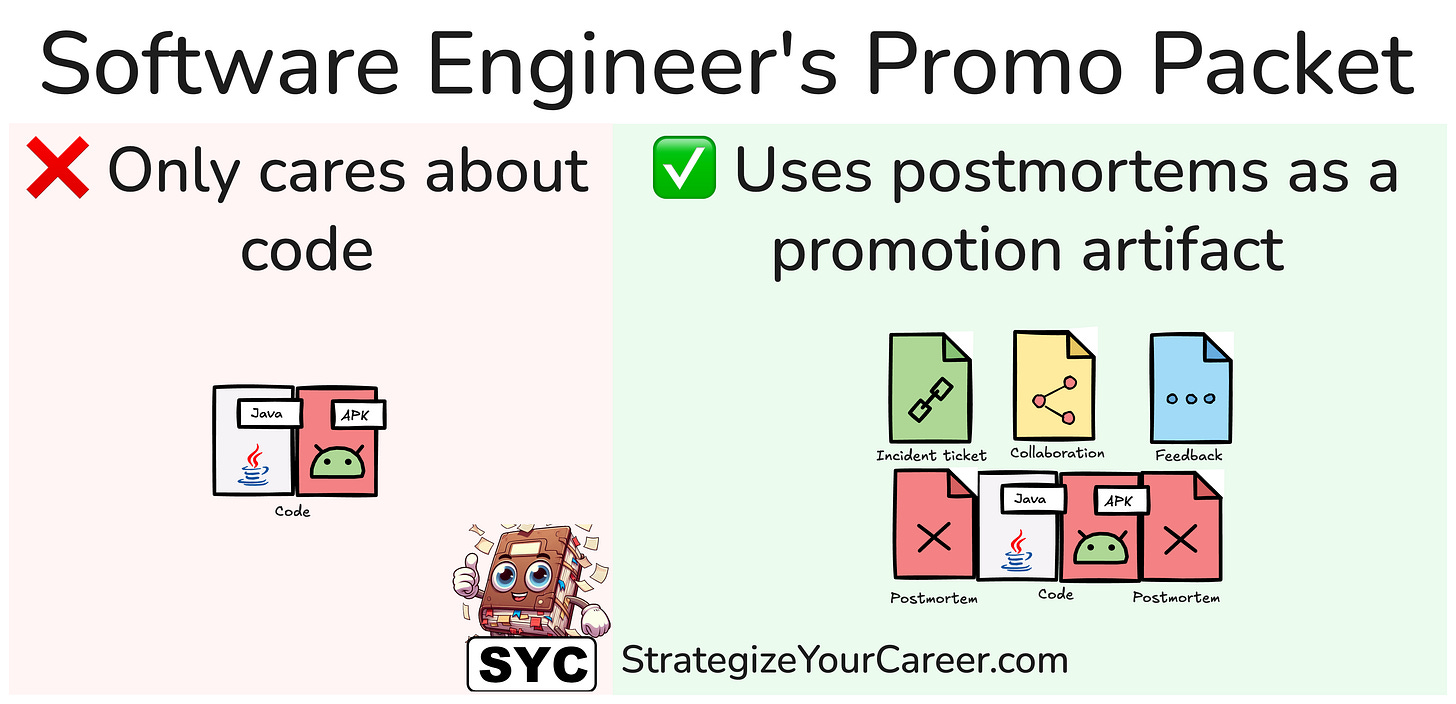

📄 The document is a promotion artifact

Most engineers think the postmortem is just paperwork. I treat it as my strongest artifact. It is visible, long-lasting, and hits all the signals that senior leadership is looking for.

These are the sections it should include

Summary

The summary goes at the top, but it is the last thing I write.

It is a high-signal brief aimed at directors and VPs. I use it to demonstrate my understanding of business context, customer impact, and long-term remediation. I treat it like I am writing an email to my director.

Graphs and Metrics

Graphs need to tell a story, not just show metrics. My first graph always shows customer impact, not service internals. That sets the tone. Then I annotate deployments, rollbacks, and anomalies. I also include graphs we wish we had. That helps justify future observability work.

I did this during a high-severity incident. Because I had debugged the same service days before, I was fast to check the metrics and present the signal cleanly. That ability came from practice and having a repeatable process.

🚀 Learn even faster

Want a higher salary, more free time, and faster learning?

This newsletter is your shortcut.

Premium subsribers are getting a template + checklist at the end of this article

Customer impact

Most engineers write “2% error rate, 300ms latency increase” and call it customer impact. That’s internal data. It doesn’t say what the user experienced.

I always ask: Did users see broken flows, timeouts, failed payments? Did support tickets spike? Did revenue dip? If you don't answer that, your postmortem is incomplete.

Diagnostic Journey

This is where you prove you're not guessing. Show your thinking. Start with the initial hypothesis, the evidence that confirmed or rejected it, and how you pivoted.

Once, I tracked a permission issue that had been apparently patched a week earlier, but never understood, and the issue happened once again. Others stopped at “fix applied.” I went deeper. This is the part of the postmortem that shows you’re not just closing tickets. You are solving problems.

Incident Timeline

The timeline is not just a dump of timestamps. It is a story of how we reacted under pressure. I always start with what changed that led to the incident. I include every delay and misstep. If we waited 20 minutes before engaging, I would make that clear and explain why. For example, “runbook lacked clarity, delayed triage.” That is not failure. That is an improvement opportunity.

We need to show care about the process, not blame. It signals that we think in systems, not individuals.

5-Why

The 5-Why is a technique that Toyota created for their internal processes and became popular. You start from the customer impact, and then keep asking "why" that happened until you reach a systemic root cause. You're not limited to doing it only 5 times.

- Why did 1234 customers have their orders lost?

(Because backend returned "200 OK" but never persisted)

- Why did the backend return "200 OK" if it had not persisted?

(Because...)You'll look inexperienced if you stop at human error. Go further and show where the system failed to protect itself.

When I review a postmortem someone else wrote, I look for exactly this. Why did no test catch it? Why was the alert unclear? Why was the runbook not followed?

Another common anti-pattern is trying to put the entire incident into the causal trees of the 5-wHy. I like including multiple 5-Why chains:

Technical Root cause: Why did the system fail like this?

Prevention: Why didn't our systems prevent this from deploying to prod?

Detection: Why did it take X time to detect the issue

Diagnosis: Why did it take X time to understand what's going on?

Mitigation: Why did it take X time to mitigate the impact?

You don't have to use them in all postmortems. But keep them in mind when you have something notorious: For example, if an issue is happening for multiple days, you must include an analysis of your detection mechanisms.

Follow-ups

This is where most postmortems fail. I do not write action items like “Improve monitoring.” I write, “Add alarm to fire when checkout P99 latency exceeds 200ms for 5 minutes. Owner: <person>. Due: <date>.” That shows clarity, ownership, and accountability.

During a postmortem I presented in an org-wide meeting, I made sure the action items were sharp and concise. No extra fluff. That made it easy for others to understand them and see that we had no gaps in our next-steps plan.

Follow-ups aren't limited to technical tasks. When I have help from someone during an incident resolution, I send a shoutout to them and I tag their manager. I try to use praise as a tool to influence technical decisions, it works much better than blame. That includes praising the people who advocate for the value of writing postmortems, even when others push back.

The postmortem process isn't a technical report. It is a leadership mechanism.

🎯 Conclusion

Premium subscribers have the template in the link after this paywall. Here’s a sneak peek: